15 July 2019 - Cited from the Financial Standard website

Retirement takes on a new meaning

To understand life beyond 66, it’s important to understand what retirement has come to mean. The Oxford English Dictionary defines retirement as “the state of condition of having left office, employment or service permanently, now especially on reaching pensionable age.”

It’s fairly textbook. The problem with it though, is the problem with all definitions. They’re only black and white on paper. In reality, there are shades of grey. To begin with, retirement, and by extension retirement income is a fairly simple proposition. People are “supposed” to stop producing income through employment around their mid 60s.

At that point, they should be eligible for the Age Pension which, when combined with their superannuation and other products to keep them ticking along – should suffice until the end of their life. But it isn’t this simple. Australians are living longer than ever before. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, life expectancy has increased by 1.5 years for Australian males and 0.9 years for Australian females in the past 10 years. The longer we live, the more pressure there is on our retirement savings. But perhaps coincidentally – or not – Australians are also working longer.

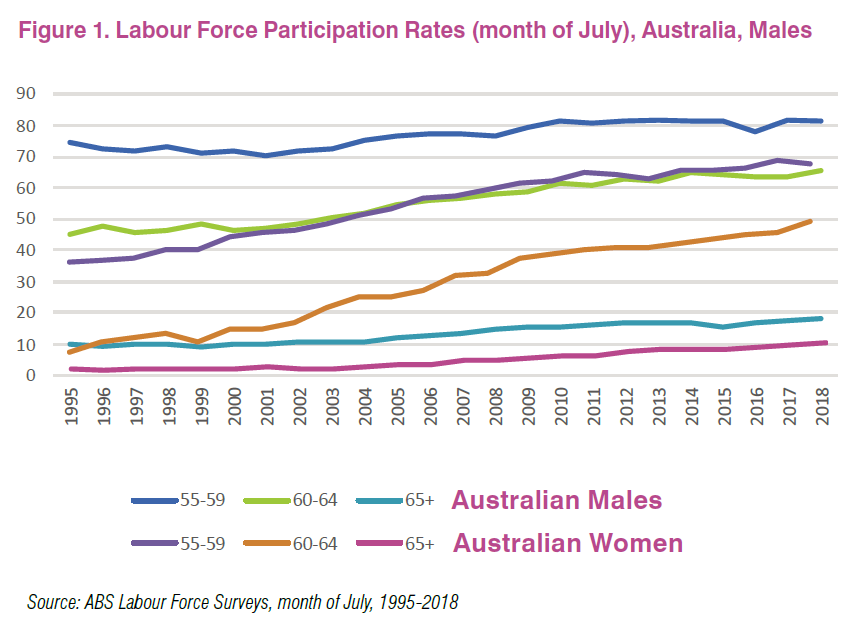

Analysis of ABS Labour Survey data by ARC Centre for Excellence in Population Ageing Research chief investigator Peter McDonald shows both men and women over 65 years old have substantially increased their participation in the labour force in the last 24 years. Add these conditions to the simple fact that many Australians retiring today saved inconsistently before Paul Keating’s mandatory super savings came into effect, and it isn’t hard to understand that retirements are varied.

While some retirees continue to work after they reach pensionable age – which increased to 66 years of age on July 1 – others can afford a life of relative comfort without the need to re-engage with the labour force. Some choose to volunteer their time to worthwhile causes and personal pursuits. Others can’t even consider the option. So with substantial diversity between the lives of many Australians beyond 66, is the word “retirement” still the most appropriate way to begin a discussion about the phase after our traditional working lives?

Shifting sands

Perhaps no demographic shift is more evident than the climbing rates of labour force participation among older Australians. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ July Labour Force Surveys, the last 24 years have seen the participation rates for both men and women over the age of 65 trend up- ward. In 1995, the participation rate for men over 65 was 10.3, and 2.9 for women. But in 2018, those numbers sat at 18.2 and 10.3 respectively.

CEPAR’s McDonald says the higher rates of engagement could be for a variety of reasons. He notes however, that conditions are ripe for older Australians to remain in the workforce, should they need to, referencing a report from the National Centre for Vocational Education Research.

“I guess the big story is that they project a very large number – over four million – of job openings over an eight year period. And that’s very largely related to the retirement of the baby boomer generation. Some two million workers will be leaving the labour force, so long as they don’t work longer. Which is what the conversation maybe is about,” McDonald says. McDonald says migration and the ageing of the generations following the baby boomers will cover some, but not all, of the hole their retirement leaves in the labour force, ensuring the trend can continue if those beyond retirement age still require the ongoing security of employment.

“A lot of the demand for new jobs is not in the immigration space. It’s not skilled work, it’s below the skill level of the immigration program. And that, I think, is the interesting issue,” he says. “Where are we going to get the workers? Lower skilled workers are going to be pretty heavily in demand in this period. And so there are various options. One of them is that the person keeps working.

“I think there’s a potential in the future for that. Employers will not be able to find the workers that they want. And so they will look at the older people. Maybe their existing employees who are thinking about retiring, and consider them working fewer hours, so they’re kind of semi-retired.” But why would they want to?

Looking for answers

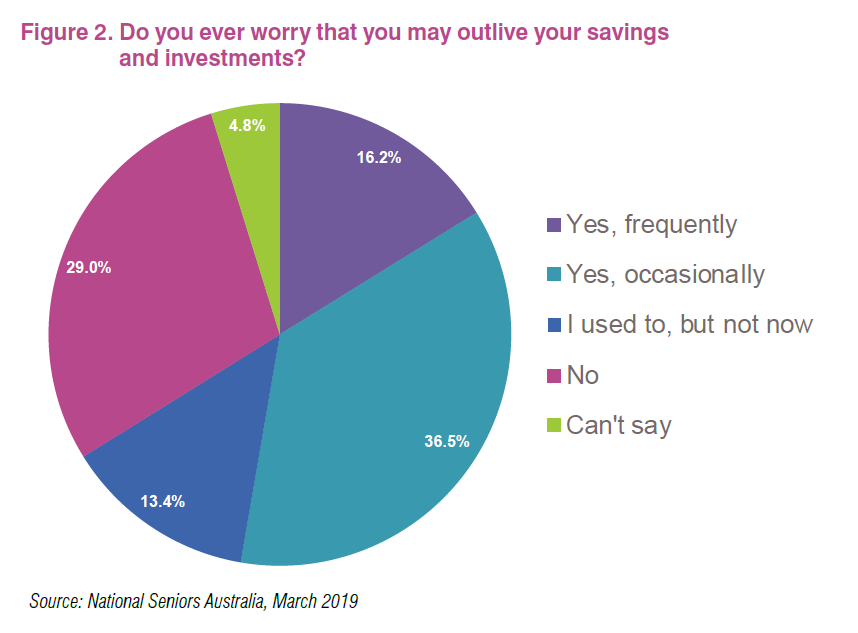

Recent Challenger and National Seniors Australia research [Figure 2] found more than half of survey respondents are worried either frequently or occasionally about outliving their savings and investments, which in part explains the decision of some to remain in the workforce, according to Challenger chair of retirement income Jeremy Cooper.

“My inclination is that people continue working for a variety of reasons. Some of it will be that they can’t afford to stop,” Cooper says. But worrying about longevity isn’t a new issue facing retirees. It is however the crux of the Government’s pivot toward a retirement income framework which serves to provide retirees with more security. A covenant position paper was followed by industry submissions last year on the topic of developing Comprehensive Income Products for Retirement (CIPRs) and retirement income strategies for members, but the Government’s proposal to legislate it by July 1 was missed due to the election.

Reading the room, the world’s second largest insurance company, Allianz, and its $2.5 trillion global investment management business, PIMCO, formed Allianz Retire+ to find a solution. Inaugural Allianz Retire+ chief executive Matthew Rady says the firm’s early research with financial advisers and their clients informed the direction of its product offering. “What we discovered through that research was that investors fear running out of money in retirement more than they fear death itself,” he says.

“And then using that research, we went back internally to the Allianz group, and looked at a range of solutions that we’ve been providing globally.” He says the firm’s first product, Future Safe, took the core of a product Allianz offered in the US and tailored it to the specific needs of Australia.

The product aims to alleviate the concerns of retirees by promising a greater degree of certainty in the outcome of their retirement savings, noting that while Australians should be incredibly proud of the superannuation system, recognition should also be afforded to the fact retirees face significant risks virtually alone when they retire.

“The way Australia’s superannuation system is constructed – through defined contribution plans – you know, the onus is on the retiree, and all of the risk sits with retirees when they retire,” Rady says.

“And so what you have is a system which leads the world in many respects in relation to the way we save for our retirement but is under developing a situation where retirees can share the risk burden as and when they retire.”

As such, Future Safe is a seven-year retirement investment product exposing retirees to market-linked investments at a level of protection they choose.

Rady says the product helps retirees continue to earn a return on their investments while warding off sequencing risk by limiting the losses that can be incurred in the early stages of retirement.

Retirees have traditionally been forced to remain exposed to assets associated with downside risk in order to make returns on what they’ve saved. But during decumulation, any losses incurred are almost impossible to recover.

“One of the biggest risks that a retiree faces when they retire is the risk that returns go backwards quickly, soon after retirement,” he says. “In retirement, the returns that you get, and the order of those returns is very, very important. Because if markets are going backwards early in your retirement, and you’re drawing down on your superannuation balance at the same time, you never get the chance to recover. So in other words, your money runs out earlier. “Pretty much every study will demonstrate how important that sequencing risk actually is.” Rady says when faced with the possibility of losing the money they’ve spent their life saving, many retirees take “a flight to safety” by moving a chunk of money into cash.

But with cash rates and bond yields sitting so low, retirees then have to contend with a stagnant portfolio. For Wealth Planning Partners director Amanda Cassar, the problem extends to other products, like lifetime annuities.

“Some of my clients are interested in lifetime annuities however the historically low interest rates can make depositing large amounts less than attractive,” she says.

Rady says taking too safe a route will still end up costing retirees in any case.

“And again, consequentially, you find that you’re going to run out of money earlier than otherwise would be the case,” he says.

“Traditionally, you’ve had to continue to take risk in your portfolio and get exposure to assets which have some downside risk associated with them, introducing that sequencing risk problem.” Future Safe is designed to protect the value of the hard earned assets that retirees have spent a lifetime accumulating, and to protect the value of those assets, effectively through a floor. Retirees can also choose – depending on the level of risk they’re prepared to take – to protect the value of their asset at either 100% or take a small amount of risk.

In return for the risk, retirees are exposed to growth markets on the upside, again up to a cap. The way Rady sees it, Allianz is promising retirees their returns will sit within a boundary which they define themselves.

“The bottom level of that boundary can be a protection on the floor of zero, with an upside to equity markets up to a cap, or if you – at the other end of the spectrum – are prepared to take a risk, say 10% of your portfolio, then we can give you returns to a large cap on the upside,” he says.

The efficacy of the pitch lies in the anxiety of retirees, which financial advisers say is rife.

“New and innovative products are vital to meet clients changing retirement needs,” Cassar says.

She says many clients are anticipating the world’s next financial meltdown, and aiming to minimise losses to reduce the force of a financial blow.

“No one wants to lose 30% of their life’s retirement savings as they get ready to step into the great unknown,” she says.

Fear vs. reality

However some are skeptical.

CPR Wealth financial adviser Luke Priddis says he understands the appeal of products which allow retirees to continue chasing returns while simultaneously protecting them from losses.

And while those products have their place, he prefers the fundamentals of good advice.

“I suppose it’s the same thing as when the GFC hit. A lot of product providers brought out products that had guaranteed returns and again, it was based on the fear of losing your capital,” Priddis says.

“At the end of the day it doesn’t matter who you are, no-one likes losing money. It’s just a tolerance to how much money you can lose in the trade-off to what you’re prepared to potentially gain along the track.”

Priddis prefers to bring the conversation back to the old KISS principle – Keep It Simple, Stupid.

“I think if you’re doing your role as an adviser properly, that’s putting all the cards on the table so that they [the client] can make their informed choices and then supporting them on what those choices are,” he says.

Many longevity products also see customers pay an annual fee of 0.85%, and may also be subject to fees on withdrawal if they take out more than the free withdrawal amount providers offer.

Priddis questions whether retirees need to pay yet more product-based fees when a good adviser could structure a similar strategy anyway.

“So obviously these sort of products are built to say ‘Okay well if I want to take this sort of risk, and this is the return I’m guaranteed, I’m only going to lose this.’ But again, are you paying more of a fee for that just because that product’s in there?” he asks.

It’s about understanding what a client’s needs and expectations are, viewing them as a pyramid, he says.

The base of the pyramid covers necessities, such as food and housing, while the middle of the pyramid may be dedicated to lifestyle preferences, such as one holiday a year. The tip of the pyramid is reserved for what Priddis refers to as “the wishes”.

“We all know sometimes you don’t get your wishes. In good years you may be able to get your wishes and in tighter years you have to be settled with your basics and a couple of things above that,” Priddis says.

“So if you can condition your clients, I suppose to the reality of life and the markets, I do sort of think that sometimes you don’t have to be paying all these additional product fees just to get something that really you could structure anyway.”

According to Challenger’s Cooper, retirement income still requires a holistic approach, one which incorporates several solutions, including the Age Pension.

“I suppose the one sort of truism about retirement income is that there’s no single silver bullet solution,” he says.

“It’s always a sort of collection of things.” Think of the Australian system as a pie, he says.

“In the pie, there’s a bit of Age Pension, there’s most likely an account-based pension from your super, and then the government’s very keen for people to do a couple of other things,” he says, referring to the retirement income framework.

Recent research produced by the annuity provider shows super is actually delivering for most Australians, with super fund members over the age of 65 collectively sitting atop an $800 billion mountain of retirement savings.

Asked whether the fears and anxieties felt by retirees were inconsistent with the data, Cooper agreed.

“I think that’s right,” he says.

“You know there are a lot of difficult calculations and behavioural biases that you’ve got to get over in order to become an extremely skilled expert in how much money you need to last over a certain distance.”

Cooper notes how the switch from a regular pay check from an employer to managing a lump sum of funds designated to last the rest of a their life increases a person’s risk aversion.

“In other words, the amount of anxiety and suffering they experience from losing $1 on the one hand, compared to the sort of pleasure and utility that they get out of making $1 becomes really disproportionate,” he notes.

“So yes, I think the data not matching the sort of individual experiences of retirement is something that we get quite used to.”

Pointing to the survey of retirees conducted by National Seniors Australia in conjunction with Challenger mentioned earlier, Cooper says the data again defies the fear felt by many retirees.

“Women seem to worry more than men. And that is not linked to how much wealth they’ve got. You might say, ‘Well, you’d expect somebody who’s only got $100,000 going into retirement to be really concerned about that. And then you’d expect somebody that’s got lots of money to be far less concerned.’ It doesn’t seem to be this,” he says.

“It doesn’t seem that much connected with the data, but it’s more psychological.”

The dictionary definition

So, how should we look at retirement?

If latest innovations are successful, perhaps those older Australians who remain in the work force longer in an effort to secure their financial future needn’t do so.

But if they aren’t, Australia’s employers sit in wait for the trend of re-engagement to continue. In the case of the latter, it may become difficult to continue using the phrase “retirement”

to describe the period of life beyond 66. Macquarie Dictionary senior editor Victoria Morgan says that consistent with all readings of the word, to retire is to leave.

“The interesting thing here is that they all share the same notion of ‘withdrawing’ or ‘retreating’ from something,” Morgan points out.

“The etymology of retire is the French word retirer meaning to pull or draw (something) back.”

Morgan says the sense of having left office, service or employment permanently has been in common usage since the mid-18th century.

However, she says there has been an exponential rise in usage of the term semi-retirement over the past three decades, including a 50-fold increase since 2011.

“The semi-retirement we’re looking at here is still paid work, not volunteering or looking after the grandkids,” she says.

“So whether it’s a means of keeping some income coming in to enable a more comfortable retirement or a way of easing in to full retirement, this is something people are choosing more and more to do.”

Director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre at the Australia National University and editor of the Australian Oxford dictionaries Amanda Laugesen says the Australian Pocket Oxford Dictionary added 550 new words in 2019, but none were a replacement for retirement.

Though, we may see a broader understanding and expansion of our sense of the word retirement to “not just be a word that refers to a complete cessation of work,” she notes.

Fundamentally, life beyond 66 is too broad to nail down an appropriate dictionary definition.

A lexicologist was quoted in Forbes magazine suggesting a different word to replace ‘retirement’ and it’s ‘retirements’. Not very imaginative perhaps but it speaks to the psychology behind life beyond 66. Retirement is not one big decision but a series of decisions, whether it’s in their investments, work commitments or lifestyle choices. That’s closer to the truth and far more inclusive.